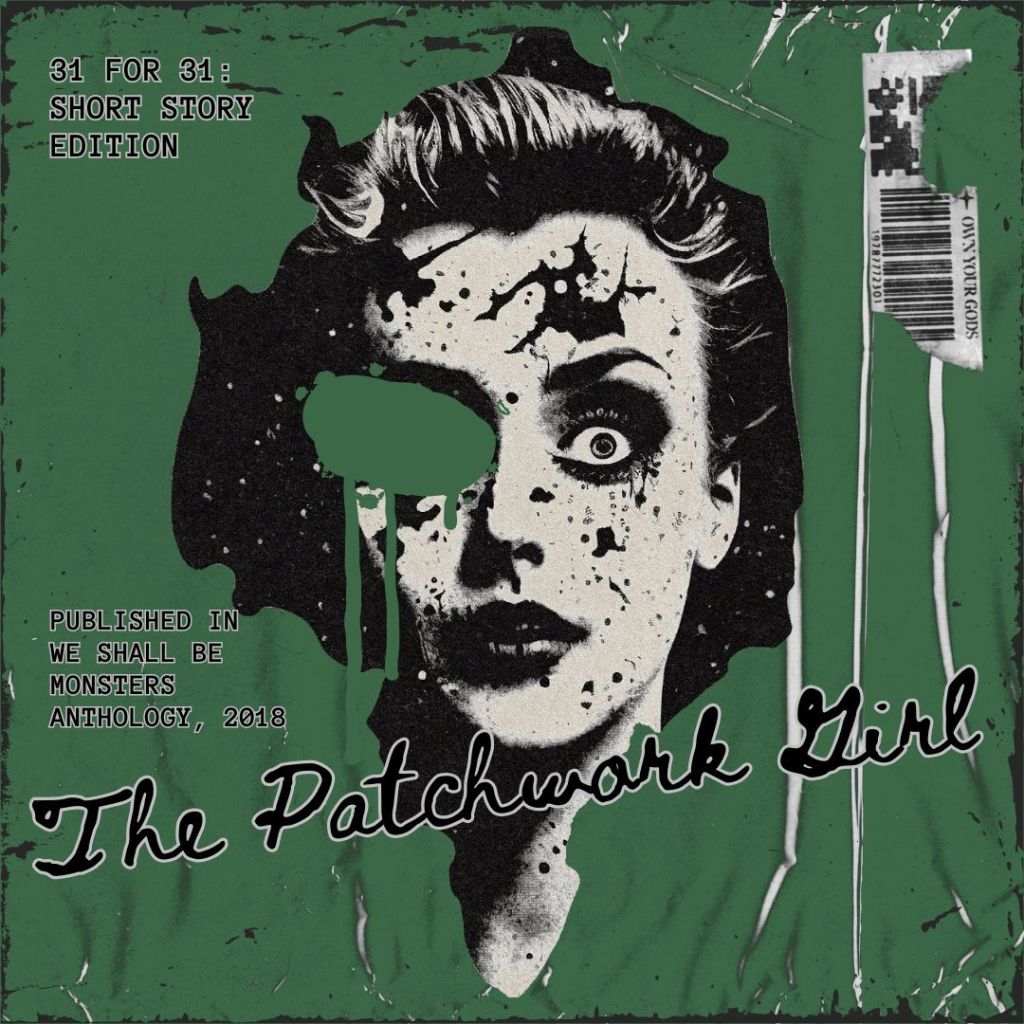

My queer Frankenstein story is next: The Patchwork Girl

This story was initially written for Derek Newman-Stille’s edited anthology for Renaissance Press back in 2018. I was friends with Derek from my master’s program, so when he posted a call for submissions asking for new interpretations on the Frankenstein mythos, I knew exactly what I wanted to do.

Part American Mary meets Silence of the Lambs, “The Patchwork Girl” follows a queer, nonbinary narrator as they become enchanted with the ‘vampire’ woman who seems to lure trans people back to her house for some unknown reason. What follows is my mix-mash of Igor and Victor Frankenstein’s relationship, and some death-defying transformations.

I had so much fun writing this, so I was even more happy to have it accepted into the anthology, and then (I believe) long-listed for a Canadian award. Didn’t win, but hey, tis always a pleasure to have been considered.

Enjoy!

The Patchwork Girl

“They say she’s a vampire.”

“And who exactly is ‘they’?”

“I am,” I chimed in. No one in the group laughed. It was a bad joke. A bad joke about neutral pronouns, which were already precarious at best. You should be more serious, Iris. Each joke may end in death. Laughter is one of the last things trans women hear before the bashing. And so on and so on. My skin already prickled with embarrassment and shame.

I went down one aisle of the poorly lit store, searching for shirts that could button over my too-large chest. Bailey and Marta went down the other aisle towards neon athletic wear. Over the hum of the Muzak and the shuffling of a dozen sneakers, I still heard parts of their conversation. They seemed fairly adamant that the woman with dark hair and a sharp nose who let us into the department store after hours to shop was a supernatural creature — a vampire, no less — rather than a godsend.

I’d first heard about The Night Shift runs when I was still working an actual night shift at the gas station. Hormones were still new to me. The always persistent fuzz above my lip became a ‘stache in no time, but I looked more like a twelve-year-old boy from a trailer park than a twenty-seven-year-old nonbinary person. I was still figuring out the right tone for my voice and the clothing I could wear. The night shift at the Gas ‘n’ Go made the perfect cover. I could still talk to people — more often than not truckers who couldn’t use a credit card or someone who wanted to know where the bathroom was — but I was mostly in the dark. I waited for my shift to end, watching YouTube videos on my phone and restocking candy.

When the woman — or vampire — came into the gas station, she had been a bright light at the end of a long night. She read me instantly as a trans person, but it wasn’t with disgust. Her slight tilt of a head and a ghost of a smile was how Marta had read me in our university class together. It wasn’t gender pieces falling out of place but falling into place. Recognition rather than revulsion.

“You ever have any nights free?” she asked.

I avoided answering. If she wasn’t a trans person herself, then she was a trans chaser. And I wasn’t interested in women anyway.

“I run a business. But it’s only open at night. You should come by.” She left a card on the counter and took her iced coffee back to her vehicle. I barely had a chance to see the plates on her van before she sped away.

The Night Shift was printed in the centre of card, indented and embossed, followed by the store’s tagline, private shopping for the private client. It listed a dilapidated department store in the middle of a strip mall along the border of Ottawa and Québec. The hours were all from midnight to dawn. A trans symbol was in one corner of the card, along with a disability sign, and two others that I didn’t recognize. I almost wrote the whole thing off as a strange invitation to a sex club, but when I ran into Bailey in my apartment after he’d stayed the night, I ended up telling him over coffee. He made me repeat the story several times before he called Marta, his dark eyes wide.

“The rumours are true. The Night Shift exists. And we’re going.”

Three weeks later, we were still shopping whenever we could get the time off. The Night Shift really was a private shopping experience for private people. A minute after midnight, the woman would show up in her dark van, or sometimes on foot carrying a large suitcase, and open the clothing store for a crowd of waiting people. She let them shop in peace while she worked the cash register. Everything had to be done in cash to keep the computer system and security system from coming on. Most of the time she screwed up the amount of change, but none of that mattered. Bailey, Marta, and I could shop for clothing. It seemed so quotidian when I tried to explain it to other people — cis ones especially — but this was so monumental. Marta wasn’t thrown out of the lingerie section. Bailey could find what he wanted without eyes on the back of his head. And I could bounce from the kids’ section to the women’s and men’s in an attempt to find something that fit my awkward body and gender without worrying. Some nights we spent the full six hours here, while other times we just went in for one specific item.

Tonight, I was trying to find a shirt. The buttons on my plaid button-up kept busting open under the strain of my chest. I could only depend on my compression binder for so much and I was getting sick of sewing buttons back on. There was no sign of surgery in my future. Gas station attendants weren’t exactly paid well. And doctors didn’t believe in nonbinary identity. While Marta and Bailey already had their future paths figured out like a tarot card spread, I was still stuck in the in-between realm of the querent. Maybe that was why they suddenly seemed to turn on the woman who had opened up the store for us and given us a new lease on life — or at least, a new impression of fashion.

“She’s gotta be a vampire,” Marta insisted. “Why else do this?”

“And she’s always up at night.”

“I’m up at night,” I said, walking over to them. “And I’m not a vampire.”

“But you’re trans. She’s not. I don’t mean vampire-vampire.” Marta rolled her eyes. “Obviously. That’s not real. But psychic vampires are. I mean, what exactly is she getting out of this arrangement?”

“The change from my twenty?” I suggested. “The feeling of doing a good deed in this transphobic world? PC points?”

“Pffft. She’s getting something more than goodie-goodie points. She’s feeding off our energy in some way. You know how people think trans people are magic.” Marta went off to list the mythological figures who were trans in some way, and then how this lore had been appropriated into a sci-fi book she’d been reading.

Bailey nodded alongside her. “I can see that. Maybe we shouldn’t keep going here. Something does feel off.”

“Yeah. You notice how almost no one is a repeat customer?”

Marta gestured around the store. We’d been there four times, which was hardly enough to establish a pattern, but I could see Marta’s point. Each time we went in, there seemed to be a new crowd of people. I thought that was exciting — more people in the trans community to know — but everyone seemed to be quiet, evasive. No one wanted to speak, except the three of us.

When a tall person came out of the change room, holding a red cocktail dress in their hands, some form of recognition panged inside of me. I pointed to them and insisted I’d seen them before. Bailey and Marta shook their heads. We all watched as the person went to the cash register to buy their dress. The woman smiled, embracing them in a hug as if they were old friends. Then she slipped something in their cellophane bag before they left.

“Was that… that was a blood bag, wasn’t it?” Marta said. “Oh my God. Oh my God. We’re leaving. Right now.”

“No,” I said, but the two of them had already stashed their clothing items at the end of the aisle. The customer service worker in me wanted to stop and clean, but I followed my friends out the door. The woman’s eyes followed us as we left without purchasing a thing. Even through the thick panelled glass of the department store window, I was still sure she was watching us.

“That was fucking close,” Marta said. “Let this be a lesson, though. Never trust cis people. Ever, ever, ever. All of them are damn vampires.”

Bailey echoed the sentiment before adding that he’d like some coffee. I followed them both, knowing that until dawn, this was the only path I could take.

#

When the sun came up, I walked back towards the strip mall. Bailey and Marta lived on the other side of town and took a bus long before I departed. They would never know that I’d doubled back to see the woman — which was as good as it was bad. I now had privacy so I could explore, but it also meant that if she was a murderer like Marta now believed, I could disappear like a ghost. I tried not to think of that possible reality, or how the papers would address me if I were to turn up missing.

I didn’t have to wait long before the low lights of the store flicked off entirely. The woman walked out wearing a trench coat, carrying her giant suitcase, and locked the door. Her dark hair was tied in a ponytail and buried under a red baseball cap. She had sunglasses perched on the edge of her nose. Though she tried to disguise herself, it was definitely her. Her suitcase was distinctive, battered and covered in patches, but there was also an aura which hung around her, one I hadn’t quite noticed until now. Whether it was supernatural or not, I still wasn’t sure.

She turned a corner and headed towards the downtown core. I followed close behind, ducking under awnings and pretending to light a cigarette every so often. I figured I wasn’t memorable. Anywhere I went, people seemed to do their best to not look at me, because looking meant deciphering my curvy body plus a moustache and short hair. Looking was too confusing. Being in-between meant I was everything, but also nothing. I banked on that feature of myself as I watched the woman walk to an apartment building with an ornate facade. The sun had fully risen. She hadn’t turned to stone or flames, so she couldn’t have been a vampire. When she stepped inside the building, I lost my eye on her entirely.

I examined the tenant list on the apartment building but found zero names. They were all numbers and floors. For a moment, I wondered if this place as an office rather than a residence, when a buzzing sounded. The lock on the door clicked open. I knew I didn’t have long so I darted inside without thinking. A camera hung in front of me, fixated on anyone who entered the foyer.

I’d be caught. Wherever she’d gone, she was watching me.

“Shit.”

“Don’t worry,” a voice came over a PA system. It was low and sensuous; familiar from the gas station. Definitely her. “You’re not in any danger. But I could use your help.”

“I. Um. Okay. I don’t think I have any choice.”

There was a beat of silence before she asked, “What’s your blood type?”

“O-.”

“You seem sure.”

“I am.”

Another beat of silence. Followed by another. She seemed to wait for me to tell her the story of my blood, but I refused. I wondered which one of us would win the standoff; I wondered which one of us had more to hide and more to lose.

“Well, okay. If you’re right, then you’re a universal donor. And you’re exactly what I need. Come on down to room six hundred. I’ll pay you for your time.”

I walked, knowing that again, this was the only path I could take.

#

She was in her office with the tall person from the store. They were naked, save for a green cloth over their genitals and chest, blocking their bits like a censorship bar. The table they were on was thick and seemed to be made of stone, rather than metal and plastic. Their body seemed to shine as the lights above them cascaded over the flecks of granite and quartz in the slab. They were clearly asleep, knocked out for some kind of surgery. The woman wore a sleek, black outfit, her hair still tied behind her slender shoulders. She wore plastic gloves that reached to her elbows and a doctor’s mask around her neck, giving her space to talk. The mask and gloves were the only items that matched the operating room decor. There were no machines to monitor heart rate or blood pressure; no typical equipment common in an operating room. The walls were littered with charts and posters depicting the human body, bisected and full of colour. There were flowers, rather than organs under the ribcage. Each image outlined chakras, not bloodlines.

“What… what is this place?”

“This is the operating theatre,” she said. “But I take the term theatre more seriously than others.”

“Is… are they…?”

“They are okay, yes.” Her use of neutral pronouns was with practiced ease. Somehow, this made me feel better. She wasn’t some strange surgeon trying to open up trans people to see if they really were unique snowflakes inside or draining their blood to consume gender magic. She wasn’t one of us, but she was next to us. Peripheral. She was a doctor, or something like it, trying to help. “We have run into a snag, though. Nin thought they were O+ but now I see that this is not the case. So I need to have a universal donor to even out what I’ve already done.”

Nowhere did I see blood. But I sensed tearing, ripping of flesh, and a state of emergency that tinted the room. Not an aura, not quite — but a feeling of pain that I could taste. Nin was in trouble and I was the only hope.

I started to roll up my sleeve without being told. The woman nodded with a pleased smile as she placed the mask over her face. She retrieved a lawn chair, painted in bright pink, and set it down next to one of her side tables lined with instruments. Each one was gold tipped and covered with a sheen of glitter. Some had pearls at the end, others had what seemed to be more quartz and diamonds. A deck of tarot cards was at the centre, the Devil card flipped up, along with the ten of pentacles.

“Inheritance. Wealth,” she said, gesturing to the card. “It’s Nin’s time to get what they deserve.”

I didn’t say anything. I watched as she withdrew a clear rod that was attached to a blood bag. She moved her hands like a magician using the clear rod as a wand. She tapped the crease of my elbow. My blood came out. The glass stained red. I felt nailed to the floor, filled with a sick sense of my body’s blood leaving me.

Then it was over. She placed a hand on my head and another card emerged. The five of cups. Two of the cups on the card were upright, while three were spilled. A man in the centre crossed his arms angrily.

“Ah,” she said. “Bad things have happened — your cups have spilled, but you need to focus on what’s in front of you.”

Again, I was silent. She added the blood to the body in front of me. The body of Nin, who was still sleeping, still dreaming in some far away, in-between place. The woman appeared by their side and did more sleight of hand magic tricks. Blood spilled everywhere. Before it pooled and turned black on the floor, the blood became dust — glitter. Nin’s body started to change. The green fabric covered their genitals fell away.

And there were no genitals. Nin was smooth like a doll, like a Ken or Barbie or both all at once. The front of their chest was devoid of nipples. All the glittered blood that had once been spilt was now clean. The woman turned away from the body on the slab, her breath heavy. Whatever she had done had taken all her strength. I could feel her exhaustion in the air, taste it like the coppery patina of pennies in a fountain.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

“I am. Nin will wake up in an hour or two.” She removed her medical gear into a blue bin on the far side of the wall. When she turned back to me, she extended her hand. “I should introduce myself, though. I’m Mary Michelle Frances Stein. But most people call me Shelly.”

#

I had coffee with Shelly until Nin woke and left. After their hug, Nin slipped an envelope into Shelly’s coat pocket. A payment for services rendered. I watched from her office window as they entered the late morning Ottawa street, now nearly barren after rush hour, and then walked into their new life. Nin would never come back to the store at night. There would be no need.

Nin was not the only person Shelly had helped. Ever since she opened The Night Shift to allow trans and disabled people to shop without worry, she realized that the clothing was only the first step of the magic, as she called it. Trans people could use clothing to transform their bodies on the surface. That was easy. But the internal matching of the external was always the last stage, always the hardest path to endure in order to be rewarded. That type of magic required someone else. So she offered her services. For payment, of course.

But there was also something else she was getting, I was sure of it. Marta’s words were like a warning on the back of my eyelids. I wanted to ignore her, but I had to ask. “Why? Why bother with all of this?”

She set down her coffee with a deliberate motion. She stared into the black void as she considered my question.

“Surely this is not the first time you’ve been asked?”

“No. But I still don’t have an answer beyond ‘why bother doing anything?’”

“That’s not an answer.”

“Exactly. But I find origin stories boring. I think you would know that most of all.”

I huffed. I thought of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health doctors in Toronto who rejected my surgical application. Gender must always have an origin. It must have an answer and a clear definitive beginning. Being two genders at once, or none of the above, made no sense to the panel of experts. So I made no sense to them.

But someone who was two at once and nothing at all was what I had watched come out Shelly’s door. Nin was real. I was real. And so was Shelly, even if she didn’t want to tell me how she had come to be this way.

“You want to know why I know I have O blood?” I asked.

She didn’t nod or say a thing. I went on.

“Because when my mom was pregnant with me, she needed those shots to balance out the proteins. Dad was O+ and mom was O-. Right from the start, I was an issue. Things couldn’t mix or balance in us. I came out as O-, and my mom always thought that meant I was always going to be like her. Sorry to disappoint, Mom. But I prefer to be in the middle. As always.”

“You prefer to be universal,” she said. “The universal donor is also the universal door.”

“Exactly.”

“I’m glad you knew your type. It’s fascinating when people don’t. I can’t fathom it. How can you be so sure of some items about yourself, but then forget others? It’s not the first time something like Nin’s issue has happened here. They thought they were universal too. But when I opened them up, I saw for myself. Not a lie, but a convenient myth they had told themselves.”

“But… there was no wound. How could you tell Nin’s blood type without a wound? And why does the blood matter?”

She smiled. “The blood, like the clothing, is part of the show. Part of the magic.”

“You keep saying that, but what does it mean?”

With a heavy sigh, she explained to me the nuances of psychic surgery. Her brand, of course. She wasn’t like one of the duplicitous cult leaders who perpetuated a medical fraud in order to leech every last penny out of poor people who didn’t know any better. She even cited a case of a con man who had contracted leprosy from doing too many fraudulent psychic surgeries, as a way of showing how irony and karma would catch up to those who used magic for trickery alone. “Cons are not what I do here. I use the pomp and circumstance of psychic surgery, but I actually pull something out or put something back in. I actually find what is useful inside of someone and then I allow their body to reach that potential.”

“Their potential? How is this not a con job too?” I asked, but soon bit back my words. I saw the smooth skin of Nin and I was awash with the memories of the operating room once again. No, the operating theatre. Surgery was always a show.

She reiterated that point over and over again. “Surgery’s a show — and gender’s a cultural artefact. Both are made up fairy tales, but they are still real. Very real. It has taken me a long time to understand the magic behind gender, and then perform surgeries in this way, but I assure you, my intentions are true.”

“How long?” I asked.

She leaned into her coffee, her body folding into sadness. The tempo of the room changed. I heard music inside my ear, Brahms or Mozart, and then I saw a face. A man’s face — but not a man’s. He was caught in-between like me. He liked the pronouns he/she but hated the skin and body that came with them.

“My husband Eugene — Genie — died before his show could end. When a bus crashed, he was one of the many injured. The paramedics cut open his shirt and found a bra underneath, along with panties now visible above the rim of his jeans. Instead of performing CPR, they laughed. He died. Story done. Poof. Over.” She sighed. “I never knew these parts of him. He kept it all hidden at the back of his closet like a dirty secret. So I opened my store at night, hoping to make amends in some way. If I could be open to others, maybe his spirit could rest. I started to feel the force of gender. Not his gender, but all genders. I started to acknowledge that we don’t just have physical bodies, but four-dimensional ones. He left the mortal world. He became matter and energy. In a way, that was what he wanted. Pure energy, magical and ethereal. But if I could synthesize a process to bring the fourth dimensional magical bodies to the surface, then no other trans person had to die to achieve it. I could help. I could find what people wanted.”

I had to laugh. It was funny, right? I wanted it to be funny. A long-extended joke. Marta putting me on, hiring an out-of-work actress to deliver a strange sci-fi monologue. A pit in my stomach would have even wanted for Marta’s other hypothesis to be right. This coffee talk was a long con and I would eventually be skinned and made into a Buffalo Bill suit. It would only be appropriate.

But Shelly was serious. I felt it inside.

“The blood is the portal,” she said. “The link between planes of existence. And I have to say… my surgery is stronger when it has access to a universal donor. How would you like a more permanent job?”

Before I answered, she divided the money that Nin had given her and handed a section of it to me. It was over one thousand dollars. Rent for the next month. I wouldn’t have to do a night shift at the gas station ever again.

But I already knew I was going to say yes.

#

For the next three months, I performed seven operations. I watched as her technique morphed from the sloppy and slap-dash emergency lifesaving surgery of Nin to the high art performance where her talent was obvious. With my blood as the universal door opener, she could access the fourth dimension without worry.

Colours spilled forth from the next surgical client, a trans man named Carl who wanted his breasts removed. Since he wanted to keep his genitals, Shelly presented him with an aura around his thighs, like a halo of good feelings. No more dysphoria. Each time he touched himself or someone touched him, bursts of colours erupted in front of his eyes. Next was a trans woman named Julie-Anne. When Shelly opened up her chest cavity in order to construct breasts, a rabbit burst forth. It hopped around the operating room until I caught it and put it in a cage. When I realized that Shelly already had the cage set up prior to the surgery, I learned that sometimes creatures moved inside of us. One day it was a rabbit, other days it was a cat, or a misshapen demon creature that Shelly had to kill the moment after it was out. Depending on what a person experienced, what they internalized as part of their life story, and what they considered to be their own special kind of magic, that was what came out of them. That was what made up their fourth dimensional bodies and their quixotic gendered souls.

The most boring surgeries were the standard ones. A trans woman named Callie who wanted a tracheal shave had a balloon float out of her and then bust. That was it. Even the atmosphere of the surgery had been lacklustre. When a trans man wanted larger hands and feet, small stones fell out of his fingers and toes, turned grey, and then turned to dust. No show whatsoever.

But each patient was grateful. They hugged Shelly as they left and sung her praises. They even started to hug me as they left, once they realized I was the assistant to the master; Igor to the gender saver Frankenstein — a neutral party in every way.

I earned more than I ever dreamed. I let the money stack up in an ornate music box my mother had given me at age seven and that I couldn’t bear to part with, even if my mother had parted ways with me. The music soon became stifled by crumpled bills and wouldn’t shut. But I couldn’t deposit that level of cash without looking suspicious. It also didn’t seem real. The magic I had witnessed from my own blood paled in comparison to commerce. One morning, as I counted, I realized I could afford my own surgery. I could remove the breasts from my chest and then buy all the shirts I wanted and needed without the fear of busting a button again. I could shop in daylight hours. I could pass as something. Maybe not a man or a woman, but my invisible identity would yield safety.

The daylight didn’t interest me anymore. I put my money back in the music box and returned to Shelly’s place, eventually letting my lease lapse and my apartment become vacated. After weeks of helping Shelly, though, she had not asked me about my own psychic surgery. Even with all of our successes, I still seemed to be a lowly Igor and nothing but.

One night, after she’d pulled a live dove from the centre of a trans man’s chest, I felt something like wings flutter inside of me. Was I filled with feathers? Would I explode under the real lights of a surgical room? I wanted to know. And I couldn’t take it anymore.

After John had left with the dove in a cage to keep as a pet familiar, I walked right over to Shelly. “Why haven’t you operated on me yet?”

“Whoa, whoa. I feel the anger. It’s blue and purple by your eyes.”

“Is it because of the blood?” I asked, ignoring her. “Am I not a universal donor if you perform surgery on me?”

She sighed. She gestured to the table and we sat down. I thought I was going to hear a lecture about how psychic surgery would make my fourth dimensional body become manifest, therefore I would no longer be in-between, so I could no longer be a helper. I expected her to reject me. Doctors had always rejected me. Why wouldn’t the magical kind of doctor be the same? But instead she grabbed my hand. Warmth radiated from her.

“You’re far stronger than you could ever imagine.”

“Because of the blood?”

“Yes and no. The more you witness here, the more you learn. The more you believe and the more magic that gets stored inside of you. If I perform surgery on you, it would be a miracle. It would be like opening a new world and watching as a new mythology comes forward.”

I felt that flutter again, but it wasn’t wings. It was like a multitude of different pathways and identities coming out of me all at once. A house of tarot cards collapsing and rebuilding. All future trajectories — everything and nothing — available before me.

I wanted that more than anything in the world. “So why won’t you work on me?”

“Because… I fear that you won’t come back after it’s done. And I’ve enjoyed our time. It’s been such a long time since anyone’s been around me.”

The loss of her husband tinged her sadness — but again, there was something more. I squeezed her hand. I sent her silent waves of approval, of hope, of understanding. Eventually, she crashed under my waves.

“I’m a monster.”

“What?”

“I’m a monster,” she repeated. “I’m Frankenstein. In the story, the creature is never the monster. That was not what Mary Shelley wanted or intended. It was science. It was technological progress. It was the horrors of discovery. I am all of those things at once. So I will always be a monster.”

“That’s…” I couldn’t argue. Her words were true. Dr. Frankenstein was the monster and all things that I had been through only confirmed that doctors were still monsters. Especially to trans people. I thought of Marta’s words about the soul-sucking nature of cis people. Shelly was cis. She was the enemy.

But she had also created so much magic. I could feel it inside of me. She had created at least half of the pathways that I now felt under my skin as emergent possibilities. I wanted to burst forward, to achieve what I wanted, but I couldn’t without her help. I never could have without her help.

“Why is the monster always a bad thing?” I asked. “Why are doctors always bad?”

“Because they exploit. Because they…”

“Because they can’t see what’s already there. Because they don’t listen to the patient. The science itself isn’t bad, though. Cis people aren’t bad. And monsters aren’t bad. But the lack of insight and understanding always leads to bad things. That’s it. Everything else is neutral.”

She tilted her head in the same way she had when she first met me. I saw so much behind her eyes. The colour of her husband’s lingerie, the patina of desire mixed with tragedy she felt for him, and my own lineage of rainbow pathways bursting forth. It made me think of a game I had played as a kid, which was really more like a story told through computer links, called The Patchwork Girl. It was about Frankenstein too, but in this version, Mary Shelley made the female monster for herself. The story was told in bits and pieces, completely out of order, and overlaid over an image of a bisected female body that acted as the home screen. It was the first game that made me realize I had desire for something more than my own body. I thought it meant I was queer. I thought it meant I was trans. But maybe it meant that I was magic inside. Or held so many magical possibilities underneath me, just like the story suggested.

In a way, all of these answers were right. And that was the real point of both the game and the operating theatre now. There were no monsters or victims or innocent people or even fully men or women anymore. There was a patchwork; a cluster; a bursting forth of so many different options that every single one was golden.

“You’re not a monster. You’re a patchwork girl,” I told her. “I’m patchwork too. We’re both made from borrowed parts and we work to stitch together and open up the fourth dimension.”

My words felt silly. They felt like reading in another language. But she smiled, as if I had finally presented her with an alternative way of seeing her life. As if I had finally given her a word for her identity that didn’t make her feel like shit.

“Okay,” she said. She touched the centre of my chest. The fluttering happened again. “Let’s open you — all of you — up.”

#

“They say she’s a vampire.”

“And who is they?” I asked, stepping close to the two trans women as they shopped in the blouse section of the store. They baulked under my gaze. Then they turned to one another, as if to confer an answer like school children before answering.

“No one. Just this woman named Marta. She runs the counselling centre.”

“And she warned us about this place.”

“Mmhmm.” I nodded. Years had passed. Marta had obtained her surgery. Gotten a better job with her new license and birth certificate, but she still worked within the community. Bailey also obtained his surgery and better identification, which he used to disappear into complacent masculinity. Their chosen pathways, their lives. Not my magic — but still no less valid. “Well, I used to know Marta. She means well. But I also know Shelly, and I can tell you that she’s no vampire.”

“Then what is she?” one of them asked. “Because this seems too good to be true.”

I smiled. I touched my chest. My breasts were now gone. But inside my front shirt pocket was a figurine that once used to belong inside a music box I had as a child, which had now been pulled out of the centre of me through psychic surgery. The tiny ballerina dancer was clear glass, but not opaque. Whenever I wanted to see inside myself, in the magic that Shelly had tapped and rearranged, all I had to do was hold the tiny glass dancer up to the light.

I held the figurine up in the store. Rainbow colours burst forth. The women gasped. They probably heard music, though not the same music I heard. I’d realized that part was different; everyone had their own stereo in their heads, but the emotions were all the same. Joy and elation. Freedom.

Pure magic.

I pocketed my glass figurine once again. The music stopped.

Their eyes were still wide. “What is… how is…?”

“You should ask Shelly.” I shot her a look across the department store. She hugged a person by the cashier and slipped them the address for her place. We would have to leave soon. I turned back towards the girls. “Just be respectful when you talk, okay? Shelly is not a vampire or a monster. She’s just like us.”

One of them scoffed. “Impossible.”

“Not so.”

“But for real, though,” the other one said. “If she’s not a vampire, then what is she?”

“A patchwork girl. Stitched together from second hand parts, but still no less real. Like me, like her.” I flicked my glass figurine once again. I left them with a cascade of light, the doors to our world now open.

END